I'm Not Enough

Defining success and detaching from the outcome

I just got out of my therapy session. I always bring a small wad of paper towels to these sessions because I always end up crying. Today, the words that made me tear up were:

"Why don't you feel like you're enough, Tash? What combination of emotions are you feeling when that's going through your mind? I could say nice things to you, but it's not my job. It's something you have to find in yourself."

I didn't have an answer for her. But after the session, I grumbled, grabbed a pen, and took out something that I had been neglecting all week: my journal. This is what I wrote.

I think it comes from the likes. Not having enough likes. Popularity. Fame. Not having enough Instagram followers. Not having sold enough copies of my book. Not being successful enough yet makes me feel I am not worthy of success. Not getting enough attention, just as I feel I didn't get enough attention as a child. I don't get invited to do enough gigs. I've never been on TV.

I love writing for the sake of writing. This was about my poisonous, deeper insecurity. I am paralyzingly anxious about my own commercial success. I tried to project these feelings onto my mother and her life, but my therapist told me that, apparently, this has nothing to do with my mother. This is my perspective of myself: I've seen external measures of success as some form of proxy for love, worth, and affection. Scrolling through Instagram only makes it worse. I know these external factors, the likes, the follows, the clicks, the money, pale in comparison to internal factors. The feeling of flow when I'm writing a piece that I'm totally in love with. Or the joy I feel when having a long meal with a friend. But society is so damn convincing.

I quickly turned to some wiser people for comfort. I tried to hold the sacred words of Patti Smith close,

"A writer, or any artist, can't expect to be embraced by the people. You know, I've done records that it seemed like no one listened to them. You write poetry books that, you know, maybe 50 people read. And you just keep doing your work because you have to. Because it's your calling."

Doing the work. The fact that I am here, right now, still keeping going. Can that convince me that I am enough? Smith shares what William Burroughs once said to her (he had already murdered his wife in Mexico City, right next to where I live),

"Keep your name clean. Don't make compromises. Don't worry about making a bunch of money and being successful. Be concerned with doing good work, and make the right choices, and protect your work. And if you build a good name, you know, eventually that name will be its own currency."

So, doing the work for an extended period of time and hoping that in 10 years, something will materialize from it.

Then I turned to Rick Rubin and his cliched book on creativity, The Creative Act: A Way of Being:

"Success has nothing to do with variables outside yourself. To move forward is an aspect of success. This happens when we finish a work, share it, and begin a new project…If we second-guess our inner knowing to attempt to predict what others may like, our best work will never appear…If we can tune in to the idea of making things and sharing them without being attached to the outcome, the work is more likely to arrive in its truest form."

Writing what I want for the sake of writing, then detaching from the outcome. Success is simply making and sharing the thing. I began to feel the dream again. I felt lighter already.

I thought for a minute. What would be the best way to detach from the outcome? How could I abandon my perfectionism? Well, I could share something that was objectively terrible writing. I could dig up a piece I published back in high school in 2012, back when I was a stuffy and academic high school student in England, writing in the voice of fancy, long, inaccessible words. If I'm not totally embarrassed by the stuff I used to write, am I really growing?

So, I am sharing that unedited piece below to do exactly that. I wrote it about the original guy who inspired me to become a writer. He arguably wrote the first personal essay, my favorite genre. And it turns out he had a couple of important things to say about our human imperfections, our insecurities, and our inadequacies as well. As cringy as it has been for me to reread this, it's a helpful reminder.

In hindsight, I want to credit basically the entire piece from a video about Michel de Montaigne by Alain de Botton. I was 17 years old when I wrote this, and checking for plagiarism online wasn't as much of a thing back then.

So, here goes nothing.

💌

P.S. Here is the answer to last week’s ranking of the males I think most highly of, from highest to lowest…

Specimen 6: Luís (Highest)

Specimen 1: The Barista

Specimen 3: The Photographer

Specimen 2: The Data Bro

Specimen 4: Runner Boy

Specimen 5: Andrzej (Lowest)

I’d like you to meet my friend…

An introduction to the Philosophies of Michel de Montaigne

Natasha Doherty 11/02/12

It is rare that I get the opportunity to write about a very close friend of mine. And to many of you who read this article, it will seem strange that I have never actually met this friend before. But I can assure you that no other person in the world, and no other text that I have ever come across, has had as much of a profound impact on me and my life as the works of the great: Michel de Montaigne. I myself do not preach to be well informed about anything like ‘philosophy’. As Montaigne encourages us to do, I have tried to accept my intellectual limitations. However, I wish to introduce you, in my own flawed and limited way, to a person that has changed my life forever.

Montaigne was born in 1533 and he accomplished many things in the first half of his life. He had been twice mayor of Bordeaux, become a lawyer, a nobleman, and had befriended the King of France. However when he turned 38 in 1571, he decided to draw himself back from the world and to retire to his castle, which was perched at the top of a wooded hill near Bergerac in Western France. There in his tower, he read, wrote and reflected on his life for 22 years until his death.

When he first resided to his study, he did not know what to write about. Yet in time he realised that he had been uniquely placed to write about and try to understand himself. In his essays, he devotes himself to conveying exactly what it is like to be Michel de Montaigne. Because he confided in me so much as his reader, I feel that this is why I consider him to be a close friend, rather than a distanced, impersonal ‘philosopher’. Through this ideal of personal identification, he successfully managed to pass on a version of the essence of himself through his most famous works ‘Les Essais’[1].

I love Montaigne so much because he seems to understand me. Whatever mood I am in, or whatever is on my mind, I simply flick through to his relevant essay and feast on the succulent meat of his advice, his warnings and his unwavering care for the wellbeing of others. He understands when I feel bad about myself. He tries to make me feel better. He values that as human beings we may feel inadequate about our bodies and that we may feel unattractive compared to our contemporaries. He appreciates that we fear being judged by others, but also that we may feel that we are simply not as clever as we should be.

‘I am a man’, he says, ‘Nothing human is foreign to me.’

I find Montaigne’s honesty with human nature very reassuring as well as amusing, but much of what he writes would never make it into a typical philosophy book. Montaigne realised that so many aspects of being human are often left out of books in an almost dishonest way. He wanted to open philosophy up. He does this, for example, by spending a lot of time talking about his penis. But although he was writing almost 500 years ago, many of Montaigne’s ideas are entirely relevant today. And despite the fact that he separated himself from the world to live in his tower, he managed to remain incredibly down to earth.

Montaigne recognized that we are surrounded by the wrong role models, who represent the physical ideal and set up false images of what we should be. Modern media examples of this today could be anyone from Kate Moss to David Beckham. He said that we focus on trying to be like these people, and inevitably we suffer from self hatred when we cannot attain these ideals. We are plagued by bodily inadequacy once more. To combat this, Montaigne devotes much of his writing to the discussion of everyday things that happened to him. In this way, he allows us and encourages us to accept the ordinary within ourselves.

‘The most terrible and violent of our afflictions is to despise our own beings.’

‘No one is free from uttering stupidities.’

Montaigne gives some rather humorous examples of people around him being rattled by insecurities. In one of his essays, he discusses how a friend of his killed himself because he was so embarrassed about letting out an enormous fart at a dinner party. He then speaks of a woman who felt so humiliated when eating in front of other people that only she ate behind a curtain. Through observing those around him, he identified that the many censored, dishonest aspects of the social world prevent us from accepting the human aspects of ourselves.

‘Kings and philosophers shit, and so do ladies.’

‘Even on the highest throne, we sit only upon our arses.’

I find the latter quote particularly heartening. The repetition of it to myself at times of worry has saved me from a lack of confidence and being overwhelmed by a fear of hierarchy. It has allowed me in many cases to do without the intimidation of others, and to find a bit of light-hearted humour in the mannerisms of those who might be seen as threatening. Montaigne went even further to say that if we are ever intimidated by somebody else, for whatever reason, we should simply imagine them sitting on the toilet.

Montaigne also understood, unlike many philosophers of his era, that having a mind and having reason could be a menace because they allow us to feel insecure. Alternatively, in order for us to forget our insecurities, he said we must remind ourselves of our true, more animalistic nature. This he sighted from studying the behaviour of the animals that lived on a farm near his castle. He said that we have much to learn from them because they lack the shame of their bodies.

Montaigne confronted many other flawed aspects of human nature, for example, the way that intellectual arrogance may lead us to want to impose our beliefs and opinions on other people. During his lifetime when the Conquistadores annexed South America, Montaigne was horrified by the intolerance of the Spanish. He argued that this prejudice could be seen in many other places today. He saw that groups of people have a sense of the normal and the abnormal, and that those who stray from ‘the norm’ are often persecuted. On the subject of prejudice, Montaigne advises us to get out of our atmosphere of single-mindedness and travel to learn from other people’s cultures. Travelling between countries, he said, should not allow us to open our minds but should enable us to see how narrow our oppressor’s minds are.

On the subject of feeling intellectually inadequate, Montaigne encouraged us to realise that many educated people are ‘just blockheads’. He argued some things, like university degrees, are false symbols of intelligence. One could be wise without ever having been to university, he said, as long as one had a sense of modesty, humility, and an acceptance of one’s intellectual boundaries. By observing and acquainting himself with the ploughmen of his fields, he saw that they were just as wise if not wiser than his noblemen friends.

‘I prefer the company of peasants because they have not been educated sufficiently to reason incorrectly.’

Montaigne observed that people who go to university are often not any happier or any wiser than those who do not. However in seeing that some people are cleverer than others, Montaigne argued that the way that we currently identify clever people is wrong. The exam system awards the wrong things; factual learning is celebrated rather than wisdom. Academic achievements, in fact, are not the sole or even a part of achieving intelligence.

In order for you to get more of a taste of what his philosophies are like, I have collected some more of his aphorisms. Some of these that follow are Montaigne’s own, but others came from the 57 that he had inscribed on the ceiling of his study. These he would look up at whilst writing to remind himself of some quintessential truths. I do not attempt to fully encompass his ideas, but some of his phrases are simply entertaining:

‘Have you ever seen a man who thinks he is wise? You have more to hope from a madman then from him’

‘Do not be wiser than necessary, but be wise in moderation.’

‘Everything is too complicated for men to be able to understand.’

‘The happiest life is to be without thought.’

‘The man who thinks he knows does not yet know what knowing is.’

‘Why torment yourself with worries that are outside of your control?’

‘There is nothing certain but uncertainty; nothing more miserable nor more proud than man.’

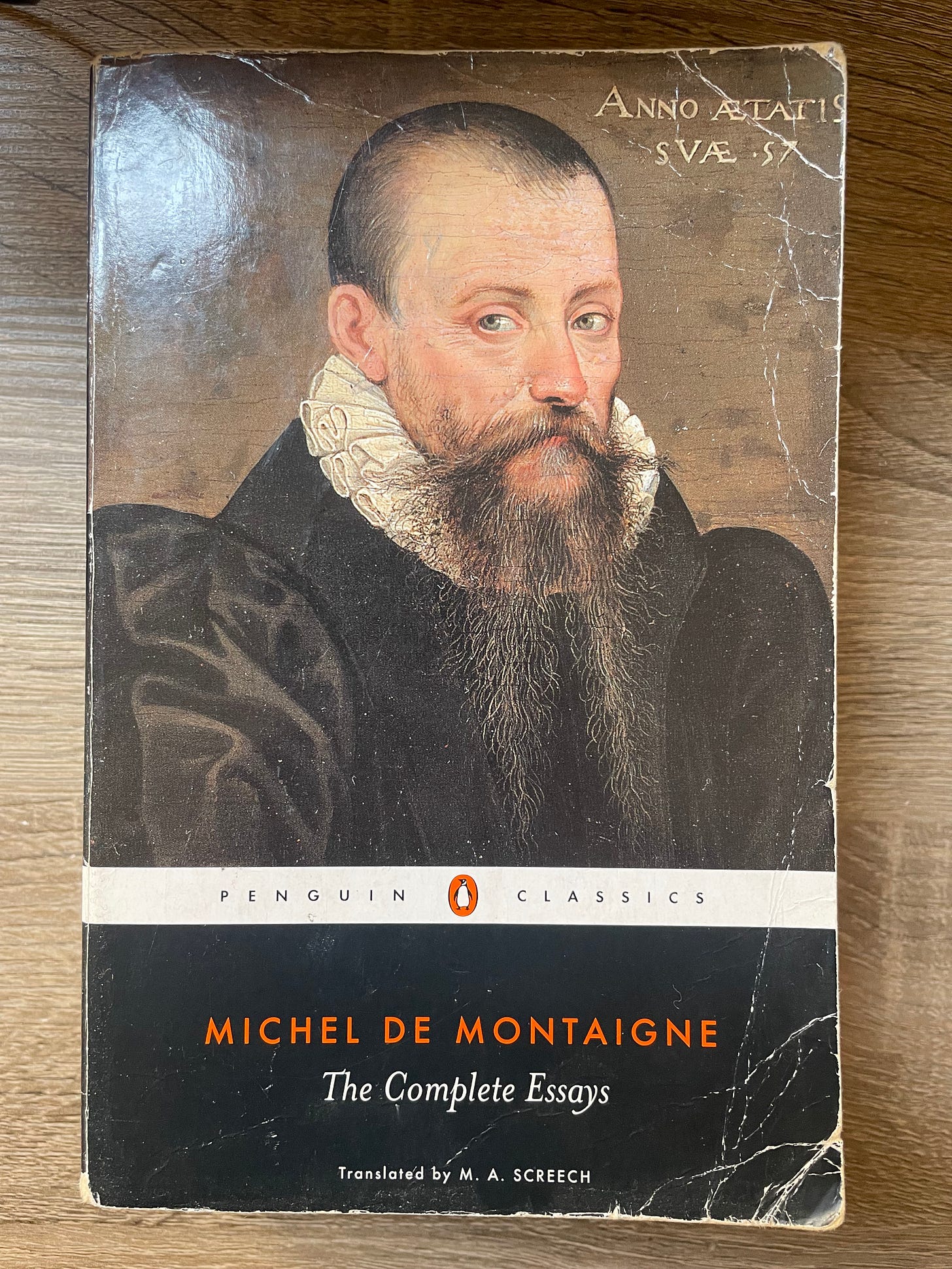

‘The Complete Essays’, translated by M.A. Screech and published most recently by Penguin Classics, cover a vast range of topics. Of all of these, my favourite and most comforting essay has been ‘On solitude’. I will now proceed with a rather long-winded quote from it, yet you must bear with me as this passage has proved to be incredibly helpful and relevant to my life. As much as I do not like to fragment Montaigne’s great work, the text that follows is taken straight from page 270 of my Penguin Classics edition. Yet I understand that only by reading his essays in their complete form can one actually receive the full richness of his philosophies,

‘When the city of Nola was sacked by the Barbarians, the local Bishop Paulinus lost everything and was thrown into prison; yet this was his prayer: ‘Keep me O Lord from feeling this loss. Thou knowest that the Barbarians have so far touched nothing of mine’. Those riches which did enrich him and those good things that made him good were still intact.

‘There you see what it means to choose treasures which no harm can corrupt and to hide them in a place which no one can enter, no one betray, save we ourselves. We should have wives, children, property and, above all, good health...if we can: but we should not become so attached to them that our happiness depends on them. We should set aside a room just for ourselves, at the back of the shop, keeping it entirely free and establishing there our true liberty, our principal solitude and asylum. Within it our normal conversation should be of ourselves, with ourselves, so privy that no commerce or communication with the outside world should find a place there; there we should talk and laugh as though we had no wife, no children, no possessions, no followers, no menservants, so that when the occasion arises that we must lose them it should not be a new experience to do without them.’

To me, this passage shows that our minds have the utmost power and control over our attitudes and our reactions to everything that affects us. It emphasises just how crucial the idea of self-image is to allow us to confront our deficiencies and to deal with our setbacks. Montaigne has demonstrated to me that basing one’s happiness on and holding onto anything in the physical world will inevitably lead to suffering because of the limited nature of our reality; things change, people move on, material possessions decay. But by tackling this with the constancy of mind and the constancy of a sense of self, he offers us a comforting opportunity to exempt ourselves from suffering. Every individual has the ultimate source of freedom and control enclosed in their own skull, which is untouchable by the hands of any other person. In the mind is where true strength lies.

‘Certainly, if he still has himself, a man of understanding has lost nothing.’

Right now, my copy of Montaigne sits on my nightstand; the cover has curled up slightly due to the book’s broken spine, so that Montaigne’s calm portrait is glancing over at me. I first heard about Montaigne after watching Alan de Botton’s video ‘Montaigne on Self-Esteem’ as part of the series ‘Philosophy: A Guide to Happiness’, which I have since revisited and used to assist with my writing of this article. Montaigne was most undoubtedly an ‘awesome dude’, but what makes him different from other philosophers is that his message stems from a man that we can trust as a friend and admire as a role model. He reassures me of what it is to be a good human being.

[1] May I interest you in ‘The Complete Essays’ translated by M.A. Screech and published by Penguin Classics in 2003?

Thank you for your candidness and thank you for your wisdom (don't let that go to your head though, per de Montaigne)

If you don't mind my sharing some thoughts:

Some of us as children were not particularly good at being 'normal'; or perhaps were but didn't get enough positive affirmation from our families our peers. I think from these was born a desire to be extraordinary and to embrace 'weirdness' and look for 'weird' heroes.

Funny enough that you mention Burroughs. He and the crowd we associate with him because idols for me simply because... damn if a crazy wierdo like Burroughs could make it in this world, surely I could, right?

But of course, Burroughs was no one to model one's life on (I figured that out soon enough) and most likely he was tortured by demons his whole life, as are many of the weirdo idols some of us cling to.

We don't have to be popular or change the world. We don't have to impress anyone. Being 'enough' is far closer to grasp than we often realise. It can still be a challenge though to define that enough and measure ourselves against, or to avoid that need to define but still have a sense of being enough.

Thanks for provoking some serious thought.

"Beautiful things don't ask for attention" - they are - and this is what I thought as I was reading this. You just don't understand how valuable your stuff already is. You look for validation in likes and shares but you have them and they are coming to be plentiful more!

As you know Tash, I never feel enough - like EVER. and this article resonated with me MOST. But I always looked up to you, your determination to write and DO IT, you are enough and you're more than enough for me. If qualitative like makes a difference - you have a qualitative like from me, because your work is transitional for me. Thank you