Warning: sexual violence and death are mentioned.

This week, on Wednesday March 8th 2023, it was International Women’s Day. Almost two years to the day since the most traumatic event of my life.

I left my house at about 3pm to attend the women’s marches in Mexico City. I was wearing purple, following the dress code my friend had told me about. As I left my apartment, I grabbed a 500 pesos note from my drawer. I knew instinctively what I had to do.

As I walked to the march, crowds of women also wearing purple and holding signs gradually gathered around me. My throat started to swell up. I hadn’t expected to get emotional already. The chanting, the energy, the spirits of all the women overwhelmed me.

“¡Señor, señora, no sea indiferente, se matan las mujeres en la cara de la gente!"

(“Sir, Madam, don’t be indifferent, they are killing women in the face of the people!”)

If you didn’t know already, I am one of the millions of women who has experienced sexual violence in Mexico. At the marches that day, I thought about it a lot. I thought about how much I had suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder these last two years. I thought about all the women who had never made it out alive, who had never been found, and who might have been saved if they had had 500 pesos on them at the time. And how many of their abusers were living free out there in the world, like my abuser was. I also thought about how unbelievable it is that I now call Mexico my home. This country is so beautiful, so vibrant and magical. But there is no justice. When unspeakably awful things happen here, there are no consequences for the perpetrators. In addition to not committing crimes in the first place, that is what needs to change.

By the time I met my friends at the Angel of Independence statue, I was crying already. I was embarrassed about being so emotional in front of them and was grateful that they held space for me. I had a good old sob, right there in front of the crowds of people. But I felt determined to make it count.

I shared my plan with Itzel, my amazing photographer friend, and her friend Renata, who I had just met. We walked around the statue, dipping through the crowds to find the right angle in the sun. I took out my 500 pesos note. I held it up to the Angel of Independence.

Another girl gave us some flowers.

That’s the story behind these pictures. Two years ago, I made it out of there. I live to tell the tale today. I am free. He didn’t get me. But I was only saved because I had money. My story is that 500 pesos, about $25USD, was the difference between me being raped or not raped. Killed or not killed. This privilege is not lost on me. It’s the harsh, damning reality of the world we live in. I think of all the missing women in Mexico, and the family members I saw that day who were marching for them. What would it have taken for them to be saved? How many of them would still be alive right now if they had had $25USD in cash?

The crowds were singing and the air was vibrant and fun. There were beautiful signs of painted uteruses with the ovaries putting up two middle fingers.

“¡El que no brinque es macho!”

(“Whoever doesn’t jump is a macho!”)

After that chant, the entire crowd would start jumping each time. There were “callaberas” (horse riders) on horseback from Veracruz. There were Otomi women, the oldest indigenous group in Mexico who also predate the Aztecs, in their colorful, traditional dress.

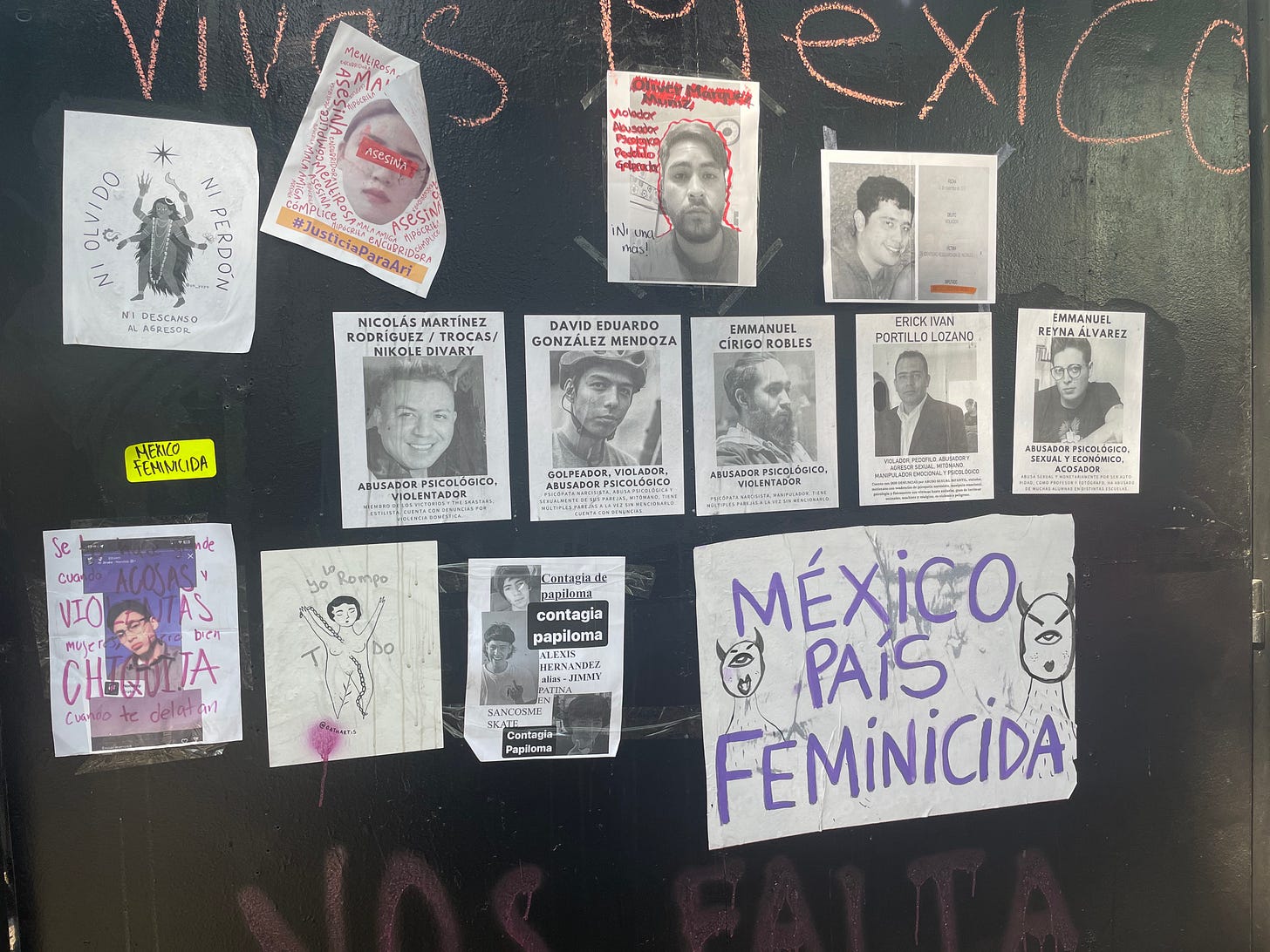

But as we headed down Reforma, to the Palacio de Bellas Artes, I couldn’t help but notice the few men in the crowd. They were often holding crosses or signs with names on them, “Jimena”, “Diana” or “mi prima” (my cousin). They wore t-shirts with a woman’s photo on them. Each one a named face of the roughly 25,000 desaparecidas (missing women) in Mexico. Families and friends travelled in groups, often wearing similar clothes, like beacons of their loved one’s voices in physical form. This was a stark contrast from the flyers stamped across the graffitied fronts of buildings, with pictures of men’s faces and their names, tagging them as “violador” (rapist), “golpeador” (beater) or “abusor psicológico” (psychological abuser).

We passed one woman holding up a sign which read,

“Escribeme el nombre de tu acosador / violador / feminicida”

“Write the name of your stalker, rapist, femicide”

People were queuing up to write names all over her body with thick, black markers. This was another emotional moment for me. I knew I wanted to write something. But the truth is, I don’t know the name of my abuser and I never will. I used Google translate on my phone. I was shaking as I wrote on her arm, “Anónimo” (Anonymous). Itzel captured this really incredible picture.

I felt the weight of my privilege as I was writing. I thought about all the women in Mexico who had experienced violence at the hands of someone whose name they would never know, like me. I thought about the women who had died at the hands of anonymous abusers. That moment was incredibly heavy. But it made me think about how I could be using my privilege more to help other people. I felt like I was carrying the weight of duty on my shoulders.

At sunset, we passed about a hundred female police officers, silently standing in a long row. Some had flowers stuffed in the pockets of their black armored suits. Others stood expressionlessly as the thousands of women marched in front of them. When we arrived in Centro, the downtown area, I saw some stores had been smashed. The air was more tense and seemed angrier there. But none of the damage done to the storefronts could compare to the gravity of what the women were fighting for. To the absolute unspeakable immensity of how many people had been murdered, how many innocent lives had been lost or ruined forever by violence and grief.

By this point, we had entered the Zocalo, the main square and the center of government. The crowd was booming. Itzel, Renata and I felt exhausted. We were ready to go home. The last sign I took a picture of was:

“Existo porque resisto”

(“I exist because I resist.”)

I thought about how I still existed because I had resisted in the moment on that hilltop in Oaxaca two years ago. I felt incredibly grateful for that, for standing up for myself so that I could have a chance of being whole again, like I feel now.

As we got in a taxi to head back to my apartment, I remembered a sign I had seen earlier that day.

“Por que? Algo tan simple cómo volver a casa es un privilegio.”

(“Why? Something as simple as coming home is a privilege.”)

p.s. A photo of Itzel being a badass photographer:

Thank you so much for sharing this experience. It means a lot - news in the US only covers American women that are abducted in Mexico. This was eye opening in a lot of ways. Great writing!